Wednesday, May 27, 2009

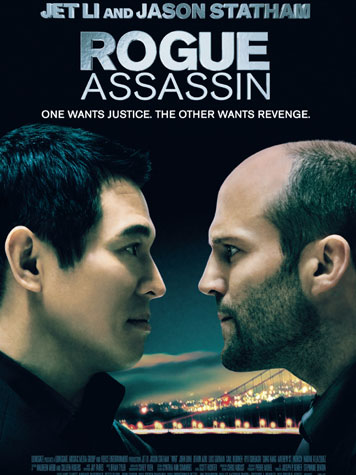

Rogue Assassin (2007)

Friday, May 22, 2009

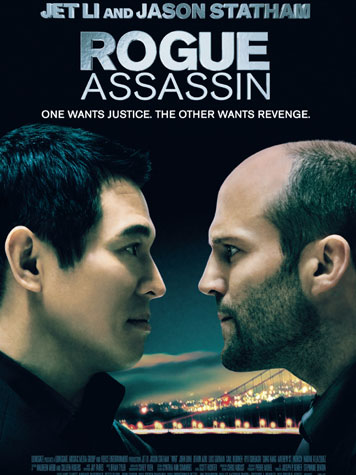

Mary Cassatt

| Mary Cassatt | |

Self-portrait by Mary Cassatt, c. 1878, gouache on paper, 23 5/8 x 16 3/16 in., Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York | |

| Birth name | Mary Stevenson Cassatt |

| Born | May 22, 1844(1844-05-22) Allegheny City, Pennsylvania, United States |

| Died | June 14, 1926 (aged 82) Château de Beaufresne, near Paris, France |

| Nationality | American |

| Field | Painting |

| Training | Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Jean-Léon Gérôme, Charles Chaplin, Thomas Couture |

| Movement | Impressionism |

Early life

Cassatt was born in Allegheny City, Pennsylvania, which is now part of Pittsburgh. She was born into favorable circumstances: her father, Robert Simpson Cassat (later Cassatt), was a successful stockbroker and land speculator, and her mother, Katherine Kelso Johnston, came from a banking family. The ancestral name had been Cossart.[1] Cassatt was a distant cousin of artist Robert Henri.[2] Cassatt was one of seven children, of which two died in infancy. Her family moved eastward, first to Lancaster, Pennsylvania, then to the Philadelphia area, where she began schooling at age six.

Cassatt grew up in an environment that viewed travel as integral to education; she spent 5 years in Europe and visited many of the capitals, including London, Paris, and Berlin. While abroad she learned German and French and had her first lessons in drawing and music.[3] Her first exposure to French artists Ingres, Delacroix, Corot, and Courbet was likely at the Paris World’s Fair of 1855. Also exhibited at the exhibition were Degas and Pissarro, both of whom would be her future colleagues and mentors.[4]

Even though her family objected to her becoming a professional artist, Cassatt began studying painting at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, at the early age of fifteen.[5] Part of her parents' concern may have been Cassatt’s exposure to feminist ideas and the bohemian behavior of some of the male students. Although about 20% of the students were female, most viewed art as a socially valuable skill; few of them were determined, as Cassatt was, to make art their career.[6] She continued her studies during the years of the American Civil War. Among her fellow students was Thomas Eakins, later the controversial director of the Academy.

Impatient with the slow pace of instruction and the patronizing attitude of the male students and teachers, she decided to study the old masters on her own. She later said, “There was no teaching” at the Academy. Female students could not use live models (until somewhat later) and the principal training was primarily drawing from casts.[7]

Cassatt decided to end her studies (at that time, no degree was granted). After overcoming her father’s objections she moved to Paris in 1866, with her mother and family friends acting as chaperones.[8] Since women could not yet attend the École des Beaux-Arts, she applied to study privately with masters from the school[9] and was accepted to study with Jean-Léon Gérôme, a highly regarded teacher known for his hyper-realistic technique and his depiction of exotic subjects. A few months later Gérôme would also accept Eakins as a student.[9] Cassatt augmented her artistic training with daily copying in the Louvre (she obtained the required permit, which was necessary to control the “copyists”, usually low-paid women, who daily filled the museum to paint copies for sale). The museum also served as a social meeting place for Frenchmen and American female students, who like Cassatt, were not allowed to attend cafes where the avant-garde socialized. In this manner, fellow artist and friend Elizabeth Jane Gardner met and married famed academic painter William-Adolphe Bouguereau.[10]

Toward the end of 1866, she joined a painting class taught by Charles Chaplin, a noted genre artist. In 1868, Cassatt also studied with artist Thomas Couture, whose subjects were mostly romantic and urban.[11] On trips to the countryside, the students drew from life, particularly the peasants going about their daily activities. In 1868 one of her paintings, A Mandoline Player, was accepted for the first time by the selection jury for the Paris Salon. This work is in the Romantic style of Corot and Couture,[12] and is one of only two paintings from the first decade of her career that can be documented today.[13] The French art scene was in a process of change, as radical artists such as Courbet and Manet tried to break away from accepted Academic tradition and the Impressionists were in their formative years. Cassatt’s friend Eliza Haldeman wrote home that artists “are leaving the Academy style and each seeking a new way, consequently just now everything is Chaos”.[10] Cassatt, on the other hand, would continue to work in the traditional manner, submitting works to the Salon for over ten years, with increasing frustration.

Returning to the United States in the late summer of 1870—as the Franco-Prussian War was starting—Cassatt lived with her family in Altoona. Her father continued to resist her chosen vocation, and paid for her basic needs, but not her art supplies.[14] She placed two of her paintings in a New York gallery and found many admirers but no purchasers. She was also dismayed at the lack of paintings to study while staying at her summer residence. Cassatt even considered giving up art, as she was determined to make an independent living. She wrote in a letter of July, 1871, "I have given up my studio & torn up my father's portrait, & have not touched a brush for six weeks nor ever will again until I see some prospect of getting back to Europe. I am very anxious to go out west next fall & get some employment, but I have not yet decided where."[15] She traveled to Chicago to try her luck but lost some of her early paintings in the Great Chicago Fire of 1871.[16] Shortly afterward, her work attracted the attention of the Archbishop of Pittsburgh, who commissioned her to paint two copies of paintings by Correggio in Parma, Italy, advancing her enough money to cover her travel expenses and part of her stay. In her excitement she wrote, “O how wild I am to get to work, my fingers farely itch & my eyes water to see a fine picture again”.[17] With Emily Sartain, a fellow artist from a well-regarded artistic family from Philadelphia, Cassatt set out for Europe again.

Impressionism

Within months of her return to Europe in the autumn of 1871, Cassatt’s prospects had brightened. Her painting Two Women Throwing Flowers During Carnival was well received in the Salon of 1872, and was purchased. She attracted much favorable notice in Parma and was supported and encouraged by the art community there: “All Parma is talking of Miss Cassatt and her picture, and everyone is anxious to know her”.[18]

After completing her commission for the archbishop, Cassatt traveled to Madrid and Seville, where she painted a group of paintings of Spanish subjects, including Spanish Dancer Wearing a Lace Mantilla (1873, in the National Museum of American Art, Smithsonian Institution). In 1874, she made the decision to take up residence in France. She was joined by her sister Lydia who shared an apartment with her. Cassatt continued to express criticism of the politics of the Salon and the conventional taste that prevailed there. She was blunt in her comments, as reported by Sartain, who wrote: “she is entirely too slashing, snubs all modern art, disdains the Salon pictures of Cabanel, Bonnat, all the names we are used to revere”.[19] Cassatt saw that works by female artists were often dismissed with contempt unless the artist had a friend or protector on the jury, and she would not flirt with jurors to curry favor.[20] Her cynicism grew when one of the two pictures she submitted in 1875 was refused by the jury, only to be accepted the following year after she darkened the background. She had quarrels with Sartain, who thought Cassatt too outspoken and self-centered, and eventually they parted. Out of her distress and self-criticism, Cassatt decided that she needed to move away from genre paintings and onto more fashionable subjects, in order to attract portrait commissions from American socialites abroad, but that attempt bore little fruit at first.[21]

In 1877, both her entries were rejected, and for the first time in seven years she had no works in the Salon.[22] At this low point in her career she was invited by Edgar Degas to show her works with the Impressionists, a group that had begun their own series of independent exhibitions in 1874 with much attendant notoriety. The Impressionists (also known as the “Independents” or “Intransigents”) had no formal manifesto and varied considerably in subject matter and technique. They tended to prefer open air painting and the application of vibrant color in separate strokes with little pre-mixing, which allows the eye to merge the results in an “impressionistic” manner. The Impressionists had been receiving the wrath of the critics for several years. Henry Bacon, a friend of the Cassatts, thought that the Impressionists were so radical that they were “afflicted with some hitherto unknown disease of the eye”.[23] They already had one female member, artist Berthe Morisot, who became Cassatt’s friend and colleague.

Cassatt admired Degas, whose pastels had made a powerful impression on her when she encountered them in an art dealer's window in 1875. "I used to go and flatten my nose against that window and absorb all I could of his art," she later recalled. "It changed my life. I saw art then as I wanted to see it."[24] She accepted Degas' invitation with enthusiasm, and began preparing paintings for the next Impressionist show, planned for 1878, which (after a postponement because of the World’s Fair) took place on April 10, 1879. She felt comfortable with the Impressionists and joined their cause enthusiastically, declaring: “we are carrying on a despairing fight & need all our forces”.[25] Unable to attend cafes with them without attracting unfavorable attention, she met with them privately and at exhibitions. She now hoped for commercial success selling paintings to the sophisticated Parisians who preferred the avant-garde. Her style had gained a new spontaneity during the intervening two years. Previously a studio-bound artist, she had adopted the practice of carrying a sketchbook with her while out-of-doors or at the theater, and recording the scenes she saw.[26]

In 1877, Cassatt was joined in Paris by her father and mother, who returned with her sister Lydia. Mary valued their companionship, as neither she nor Lydia had married. Mary had decided early in life that marriage would be incompatible with her career. Lydia, who was frequently painted by her sister, suffered from recurrent bouts of illness, and her death in 1882 left Cassatt temporarily unable to work.[27]

Cassatt’s father insisted that her studio and supplies be covered by her sales, which were still meager. Afraid of having to paint “potboilers” to make ends meet, Cassatt applied herself to produce some quality paintings for the next Impressionist exhibition. Three of her most accomplished works from 1878 were Portrait of the Artist (self-portrait), Little Girl in a Blue Armchair, and Reading Le Figaro (portrait of her mother).

Degas had considerable influence on Cassatt. She became extremely proficient in the use of pastels, eventually creating many of her most important works in this medium. Degas also introduced her to etching, of which he was a recognized master. The two worked side-by-side for awhile, and her draftsmanship gained considerable strength under his tutelage. He depicted her in a series of etchings recording their trips to the Louvre. She had strong feelings for him but learned not to expect too much from his fickle and temperamental nature. The sophisticated and well-dressed Degas, then forty-five, was a welcome dinner guest at the Cassatt residence.[28]

The Impressionist exhibit of 1879 was the most successful to date, despite the absence of Renoir, Sisley, Manet and Cézanne, who were attempting once again to gain recognition at the Salon. Through the efforts of Gustave Caillebotte, who organized and underwrote the show, the group made a profit and sold many works, although the criticism continued as harsh as ever. The Revue des Deux Mondes wrote, “M. Degas and Mlle. Cassatt are, nevertheless, the only artists who distinguish themselves…and who offer some attraction and some excuse in the pretentious show of window dressing and infantile daubing”.[29]

Cassatt displayed eleven works, including La Loge. Although critics claimed that Cassatt’s colors were too bright and that her portraits were too accurate to be flattering to the subjects, her work was not savaged as was Monet's, whose circumstances were the most desperate of all the Impressionists at that time. She used her share of the profits to purchase a work by Degas and one by Monet.[30] She exhibited in the Impressionist Exhibitions that followed in 1880 and 1881, and she remained an active member of the Impressionist circle until 1886. In 1886, Cassatt provided two paintings for the first Impressionist exhibition in the United States, organized by art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel. Her friend Louisine Elder married Harry Havemeyer in 1883, and with Cassatt as advisor, the couple began collecting the Impressionists on a grand scale. Much of their vast collection is now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.[31] She also made several portraits of family members during that period, of which Portrait of Alexander Cassatt and His Son Robert Kelso (1885) is one of her best regarded. Cassatt’s style then evolved, and she moved away from Impressionism to a simpler, more straightforward approach. She began to exhibit her works in New York galleries as well. After 1886, Cassatt no longer identified herself with any art movement and experimented with a variety of techniques.

Later life

Cassatt's popular reputation is based on an extensive series of rigorously drawn, tenderly observed, yet largely unsentimental paintings and prints on the theme of the mother and child. The earliest dated work on this subject is the drypoint Gardner Held by His Mother (an impression inscribed "Jan/88" is in the New York Public Library),[32] although she had painted a few earlier works on the theme. Some of these works depict her own relatives, friends, or clients, although in her later years she generally used professional models in compositions that are often reminiscent of Italian Renaissance depictions of the Madonna and Child. After 1900, she concentrated almost exclusively on mother-and-child subjects.[33]

In 1891, she exhibited a series of highly original colored drypoint and aquatint prints, including Woman Bathing and The Coiffure, inspired by the Japanese masters shown in Paris the year before. (See Japonism) Cassatt was attracted to the simplicity and clarity of Japanese design, and the skillful use of blocks of color. In her intrepretation, she used primarily light, delicate pastel colors and avoided black (a “forbidden” color among the Impressionists). A. Breeskin, of the Smithsonian Institution, notes that these colored prints, “now stand as her most original contribution… adding a new chapter to the history of graphic arts…technically, as color prints, they have never been surpassed”.[34]

The 1890s were Cassatt's busiest and most creative time. She had matured considerably and became more diplomatic and less blunt in her opinions. She also became a role model for young American artists who sought her advice. Among them was Lucy A. Bacon, whom Cassatt introduced to Camille Pissarro. Though the Impressionist group disbanded, Cassatt still had contact with some of the members, including Renoir, Monet, and Pissarro.[35] As the new century arrived, she served as an advisor to several major art collectors and stipulated that they eventually donate their purchases to American art museums. Although instrumental in advising the American collectors, recognition of her art came more slowly in the United States. Even among her family members back in America, she received little recognition and was totally overshadowed by her famous brother.[36]

Mary Cassatt's brother, Alexander Cassatt, (president of the Pennsylvania Railroad from 1899 until his death) died in 1906. She was shaken, as they had been close, but she continued to be very productive in the years leading up to 1910.[37] An increasing sentimentality is apparent in her work of the 1900s; her work was popular with the public and the critics, but she was no longer breaking new ground, and her Impressionist colleagues who once provided stimulation and criticism were dying off. She was hostile to such new developments in art as post-Impressionism, Fauvism and Cubism.[38]

A trip to Egypt in 1910 impressed Cassatt with the beauty of its ancient art, but was followed by a crisis of creativity; not only had the trip exhausted her, but she declared herself "crushed by the strength of this Art", saying, "I fought against it but it conquered, it is surely the greatest Art the past has left us ... how are my feeble hands to ever paint the effect on me."[39] Diagnosed with diabetes, rheumatism, neuralgia, and cataracts in 1911, she did not slow down, but after 1914 she was forced to stop painting as she became almost blind. Nonetheless, she took up the cause of women's suffrage, and in 1915, she showed eighteen works in an exhibition supporting the movement.

In recognition of her contributions to the arts, France awarded her the Légion d'honneur in 1904.

She died on June 14, 1926 at Château de Beaufresne, near Paris, and was buried in the family vault at Mesnil-Théribus, France.

As of 2005, her paintings have sold for as much as $2.87 million.

THANKS TO: WIKIPEDIA

Thursday, May 14, 2009

Monday, May 11, 2009

Vantage point (2008) mp4

The President of the United States is in Salamanca, Spain, about to address the city in a public square. We see a plain-clothes cop, his girlfriend with another man, a mother and child, an American tourist with a video camera, and a Secret Service agent newly returned from medical leave. Shots ring out and the President falls; a few minutes later, we hear a distant explosion, then a bomb goes off in the square. Those minutes are retold, several times, emphasizing different characters' actions. Gradually, we discover who's behind the plot. Is the Secret Service one step ahead, or have the President's adversaries thought of everything?

Sunday, May 10, 2009

Stonehenge

The megalithic ruin known as Stonehenge stands on the open downland of Salisbury Plain two miles (three kilometres) west of the town of Amesbury, Wiltshire, in Southern England. It is not a single structure but consists of a series of earth, timber, and stone structures that were revised and re-modelled over a period of more than 1400 years. In the 1940s and 1950s, Richard AtkinsonArchaeological Report (10) published by English Heritage. proposed that construction occurred in three phases, which he labelled Stonehenge I, II, IIIa, IIIb, and IIIc. This sequence has recently been revised in

Phase I (2950-2900 BCE)

Stonehenge Phase I (2950-2900 BCE)

The earliest portion of the complex dates to approximately 2950-2900 BCE (Middle Neolithic). It is comprised a circular bank, ditch, and counterscarp bank of about 330 feet (100 metres) in diameter. Just inside the earth bank is a circle of the 56 Aubrey holes that held wooden posts.

Phase II (c. 2900-2400 BCE)

After 2900 BCE and for approximately the next 500 years (until 2400 BCE), post holes indicate timber settings in the centre of the monument and at the north-eastern entrance. The Aubrey Holes no longer held posts but were partially filled, some with cremation deposits added to the fill. The numerous post holes indicate timber structures but no clear patterns or configurations are discernible that would suggest their shape, form, or function.

Phase III (c. 2550-1600 BCE)

Stonehenge Phase III, sub-phase 3ii (c. 2550-1600 BCE)

The Sarsen Circle and the Trilithon Horseshoe

During Phase III the monument underwent a complicated sequence of settings of large stones. The first stone setting comprised a series of Bluestones placed in what are known as the Q and R Holes (sub-phase 3i). These were subsequently dismantled and a circle of Sarsens and a horseshoe-shaped arrangement of Trilithons erected (sub-phase 3ii).

The Sarsen Circle, about 108 feet (33 metres) in diameter, was originally comprised of 30 neatly trimmed upright sandstone blocks of which only 17 are now standing. The stones are evenly spaced approximately 1.0 to 1.4 metres apart, and stand on average 13 feet (4 metres) above the ground. They are about 6.5 feet (2 metres) wide and 3 feet (1 metre) thick and taper towards the top. They originally supported sarsen lintels forming a continuous circle around the top. Each lintel block has been shaped to the curve of the circle. The average length of the rectangular lintels is 3.2 metres (10' 6"). The lintels were fitted end-to end using tongue-and-groove joints, and fitted on top of the standing sarsen with mortice and tenon joints. The Sarsen Circle with its lintels is perhaps the most remarkable feature of Stonehenge in terms of design, precision stonework, and engineering.

Part of the outer Sarsen Circle with lintels in place.

In front of them are stones of the Bluestone Horseshoe (see below)

Sarsen stones are hard-grained sandstone with a silaceous cement. They were probably brought to the site from the Marlborough Downs, about 30 kilometres to the north of Stonehenge.

The Trilithons are ten upright stones arranged as five freestanding pairs each with a single horizontal lintel. They were erected within the Sarsen Circle in the form of a horseshoe with the open side facing north-east towards the main entrance of the monument. They were arranged symmetrically and graded in height; the tallest is in the central position. Only three of the five Trilithons are now complete with their lintels. The other two both have only one standing stone with the second stone and lintel lying on the ground.

Two of the Trilithons

In front of them can be seen two of the upright bluestones, which originally formed an oval inside the horseshoe of Trilithons

Bluestones may have been added next (sub-phase 3iii) but were subsequently removed.

Stonehenge Phase III, sub-phase 3iv (c. 2550-1600 BCE)

The Bluestone Oval and the Bluestone Circle

In sub-phase 3iv, a Bluestone Oval added within Trilithon Horseshoe and a Bluestone CircleTrilithon Horseshoe but inside the Sarsen Circle. added outside the Trilithon Horseshoe but inside the Sarsen Circle.

The term "Bluestone" refers to various types of mostly igneous rocks including dolerites, rhyolites, and volcanic ash. It also includes some sandstones. The Bluestones at Stonehenge are believed to have originated from various outcrops in the Preseli Hills in Pembrokeshire in Wales. How they were transported to the site at Stonehenge has been the subject of much speculation.

Stonehenge Phase III, sub-phase 3v (c. 2550-1600 BCE)

The Bluestone Horseshoe

In sub-phase 3v, an arc of stone was removed from the Bluestone Oval to form a Bluestone Horseshoe.

Stonehenge Phase III, sub-phase 3vi (c. 2550-1600 BCE)

The Y and Z Holes

In the final sub-phase (3vi), two circles, one inside the other, known as the Y and Z Holes were dug for the placement of stones but were never filled.

Probably also dating to Phase III are the four Station Stones (only two of which survive, and one of them has fallen). These sarsen stones stood just inside the Bank on more or less the same line as the Aubrey Holes. Two of the Station Stones were surrounded by circular ditches 10 to 12 metres in diameter. These have caused the area enclosed by the ditch to appear mound-like and have lead to the erroneous identification of each mound as a burial barrow.

Assigned to Phase III are also Stoneholes D and E and the recumbent sarsen known as the Slaughter Stone located on the north-east side in a break in the bank-and-ditch in what is regarded as the main entrance of the monument.

At this time was also laid out an earthwork known as the Avenue that extends north-east from the break in the bank-and-ditch.

Located further along the Avenue , and most likely dating to this period, is the so-called Heel Stone (Stone 96). The sarsen Heel Stone is approximately 16 feet high (4.88 metres), with another 4 feet (1.22 metres) buried below ground. The Heel Stone is surrounded by a circular ditch of approximately the same dimensions as the ditch surrounding each of the two Station Stones. The stone now leans out of vertical but most likely once stood upright. Originally, the Heel Stone may have been paired with another stone now missing (Stonehole 97).

Heel Stone

Finally, mention should be made of the so-called Altar Stone, a large dressed block of sandstone that lies embedded in the ground within the Trilithon Horseshoe and "in front of" of the central and largest Trilithon pair. Two fallen stones now lie across it. The stone is believed to be Cosheston Beds Sandstone from south Wales, and is the only example of this type of stone at Stonehenge. It is 16 feet long (4.9 metres), 3 feet 6 inches wide (1 metre), and 1 foot 9 inches thick (0.5 metres).

Stonehenge at the end of Phase III

(image from Mohen, p. 131)

thanks to:Dr. Christopher L. C. E. Witcombe

Professor, Department of Art History, Sweet Briar College, Virginia

Friday, May 8, 2009

Enrique music videos

http://www.megaupload.com/?d=Y325F2ZB

Wednesday, May 6, 2009

Entrapment (1999) 400mb

Following the theft of a highly-secured piece of artwork, an agent convinces her insurance agency employers to allow her to wriggle into the company of an aging but active master thief. Connery's burglar takes her on suspiciously and demands rigorous training before their first job together--stealing a highly-valued mask from a chichi party. Their deepening attraction and distrust could tear apart their partnership but the promise of a bigger prize (some eight billion odd dollars) by Zeta-Jones keeps the game interesting. Only, who's playing with whom?

The Italian Job

In Venice, Italy, a team of expert theives pulls a daring heist of 35 million dollars in bars of gold. One of the theives betrays his companions and swipes the gold for himself. One year later, in Los Angeles, the surviving team members create a smart and devious plan to steal back the gold and get their revenge on the traitor.

Saturday, May 2, 2009

Here on Earth (2000)

.jpg)

The lives of three young people - a rich student, a girl from the "wrong side of the tracks" and her boyfriend - unexpectedly intersect during one fateful summer in the romantic drama "Here on Earth." Kelley Morse (Chris Klein), who is cocky and brash, normally would never have crossed paths with the residents of a small town near his posh private school. But when he takes his shiny new Mercedes out for a drive, he locks horns with some of the locals, including Jasper (Josh Hartnett). As Jasper's willful girlfriend Samantha (Leelee Sobieski) looks on, Kelley and Jasper engage in a dangerous car race that turns disastrous, leaving a popular diner owned by Samantha's mother in ruins. Kelley and Jasper are sentenced to a creatively ironic but fitting punishment: They must help rebuild the diner. Not only does this ruin Kelley's summer plans, he also must board at the home of his rival, Jasper. Kelley begins to fulfill his "sentence," but refuses to have anything to do with Jasper and his parents. When Kelley again encounters Samantha, the attraction is immediate and strong. First love blossoms in the Berkshire woods ("a little bit of heaven, here on earth," Samantha calls the pastoral setting), angering Jasper, who has known Samantha practically his entire life. These new feelings and the romantic triangle that develops are only the beginning of a new journey for Kelley, Samantha and Jasper, as they ultimately make life-changing discoveries about themselves and each other

A Walk to Remember (2002) 350 mb

.jpg)